“Lucky Lindy”

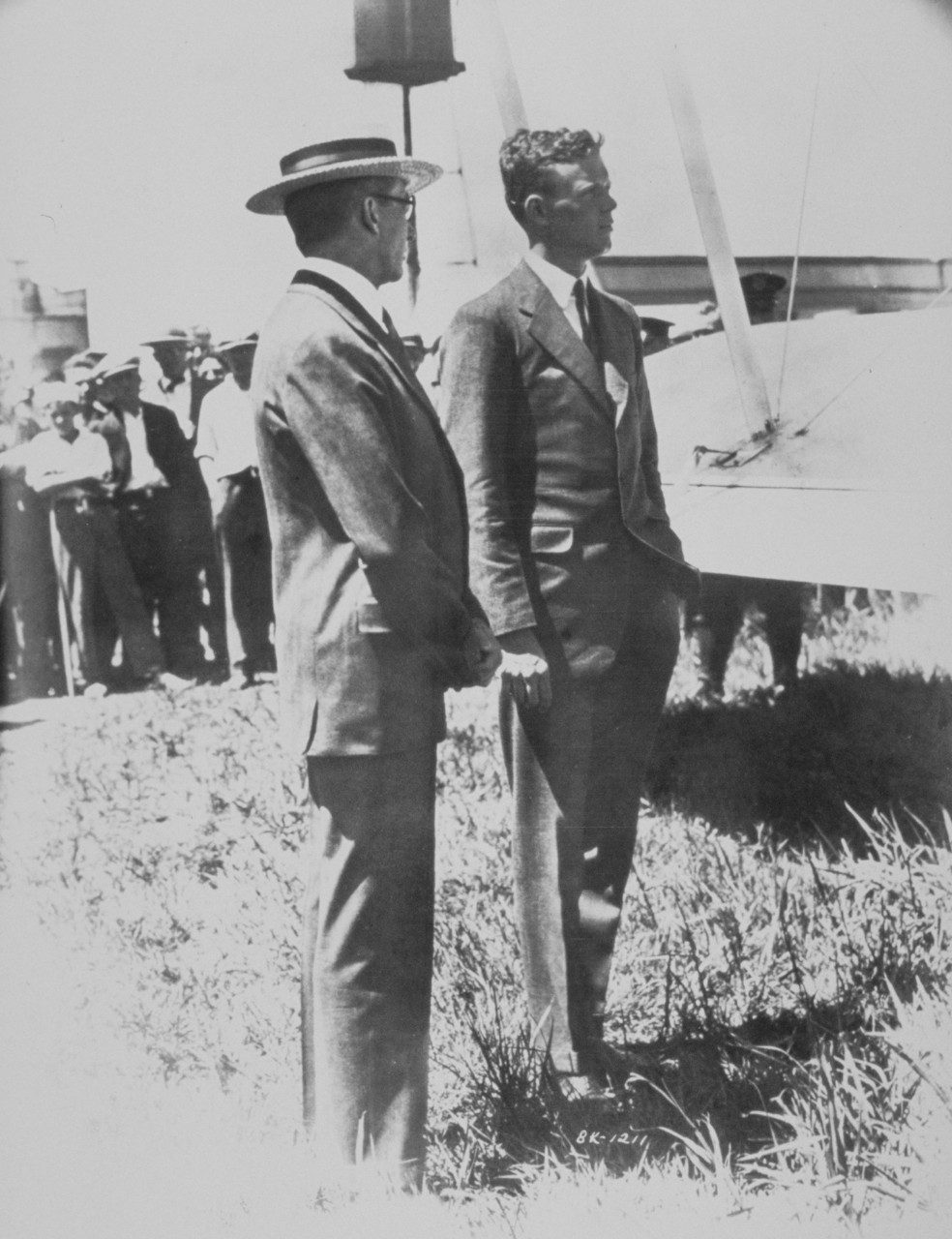

Charles Lindbergh became the first true global celebrity—and sparked a worldwide craze for flying—with his 1927 nonstop solo flight from New York to Paris in the custom-built Spirit of St. Louis. With that plane donated to the Smithsonian Institution the following year, and with Lucky Lindy’s de-facto role as the global ambassador for aviation expanding by the month, he needed a new, more versatile plane to suit his expanding horizons. He turned to Lockheed.

Lockheed was already known as an innovative designer and manufacturer of some of the world’s finest and fastest aircraft. By the late 1920s, the Lockheed Vega had not only set and broken speed records, it had been flown by George Hubert Wilkins in his quest to fly over the Arctic Sea and the North Pole. Impressive as the Vega was, Lindbergh needed something entirely new to meet his next challenge.

The Lockheed Sirius

Lindbergh wanted his new plane to be able to make a nonstop flight across the United States, as well as scout new air routes to China. It was up to Lockheed to invent the technology to meet his needs. Lindbergh’s list of custom touches included a tandem cockpit with dual controls and sliding canopy to accommodate him and his co-pilot—his seven-month’s-pregnant wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh. The fuselage needed to be big enough to allow for full use of parachutes in case they needed to make a mid-air exit. Room also had to be made for state-of-the-art navigation equipment and a small generator that could power the Lindberghs’ electrically warmed flight suits.

Lockheed chief engineer Gerard Vultee designed the Lockheed 8 Sirius based on Lindbergh’s specifications. Slightly smaller than the Spirit of St. Louis—just shy of 43 feet to the St. Louis’s 46—the Sirius was capable of traveling 185 miles per hour compared to the St. Louis’s top speed of 133 mph. It was delivered in April 1930, and within days Charles and Anne embarked from Los Angeles, arriving in New York City 14 hours, 45 minutes, and 32 seconds later—breaking the previous record by 3 hours.

Crossing the Pacific

Turning his sights toward Asia, Lindbergh sought more modifications to his Sirius the following year. In advance of a flight to China, via a northerly route that would also take the Lindberghs (his wife, Anne, would again be his co-pilot) to Canada and Japan, the Sirius was retrofitted as a sea plane, with pontoons added in place of wheels. The engine was upgraded from a 450 horsepower to 575, and a new long-range radio was added to the communications equipment. As elsewhere, Lindbergh was greeted in China as a celebrity. But when his flights took him over areas of the Yangtze River struck by the worst flooding seen in decades, Lindbergh canceled his social functions and used the Sirius to deliver medicine and supplies to areas no one else could reach.

When the Lindberghs were stopped in Hankou, near where the Yangtze and Han rivers meet, the Yangtze’s current was too great to safely moor. The British carrier HMS Hermes offered to keep the plane aboard with its own seaplanes, but the Sirius was nearly capsized as the Hermes unloaded it. It was a hardy plane, but its fuselage and wings suffered enough damage that Lindbergh judged it unsafe to fly. Rather than trust the repairs to local mechanics, Lindbergh had the plane shipped back to California to be repaired by Lockheed.

With the plane restored to full working condition, Lindbergh continued to fly the Sirius through the 1930s to map new airline routes. But when America was drawn into World War II, Lindbergh sought to serve his country. Lockheed’s planes had served Lindbergh well for exploration and research. Would they rise to the task when Lucky Lindy went to war?

Lindbergh Pilots the Lightning

Due to his earlier objections to America’s support of the Allied cause, Charles Lindbergh was not permitted to join the military. But that didn’t mean he couldn’t find ways to contribute to the war effort; he served as a wartime consultant for many aviation companies, and in 1944 Lindbergh visited the Pacific theater. He was officially given “observer status,” but he flew as many as fifty combat missions during the war.

Lindbergh piloted the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, the only American fighter in production throughout the entire war. During his time with the 475th Fighter Group of the Fifth Army Air Force, Lindbergh’s familiarity with Lockheed craft allowed him to instruct his fellow pilots on how to increase the Lightning’s range and fuel efficiency. If any had previously questioned the presence of a civilian celebrity pilot, Charles Lindbergh soon gained their respect. After the war, Lindbergh continued to serve as a consultant to the Air Force and to commercial airline companies.

Charles Lindbergh’s Lockheed Sirius joined the Spirit of St. Louis in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum when it opened on the National Mall in 1976. Lindbergh’s legacy lives on today, though some of his records have long since been surpassed, with Lockheed Martin technology playing a leading role. The current transcontinental air speed record is held by pilots Ed Yeilding and Joseph Vida, who flew the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird to its retirement home at the Smithsonian on March 6, 1990, arriving in Washington, D.C., from Los Angeles in 67 minutes, 54 seconds.

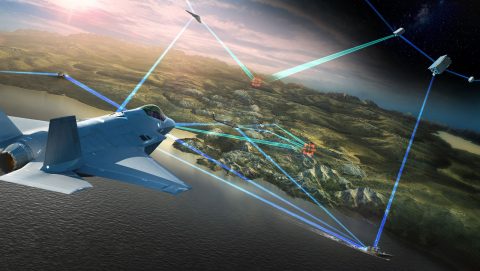

The successor to Lindbergh’s P-38 Lightning also continues to break aviation records. Introduced in 2006, the F-35 Lightning II embodies the same combination of versatility, innovation and power that made the P-38 the most feared fighter of World War II. Just as the P-38 was built to handle numerous combat roles with ease —from air-to-air combat and dive bombing to close air support and photo reconnaissance—the F-35 is adopting those roles, and more, in today’s networked battlespace.

Charles Lindbergh was known for coaxing airplanes to do the impossible. One can’t help but wonder what Lucky Lindy would have thought of a jet that could go from supersonic flight to a vertical landing in a matter of minutes.

Sources and Additional Reading

- Berg, Lindbergh

- Boyne, Beyond the Horizons

- Lindbergh, North to the Orient

- The Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum, Washington, D.C.